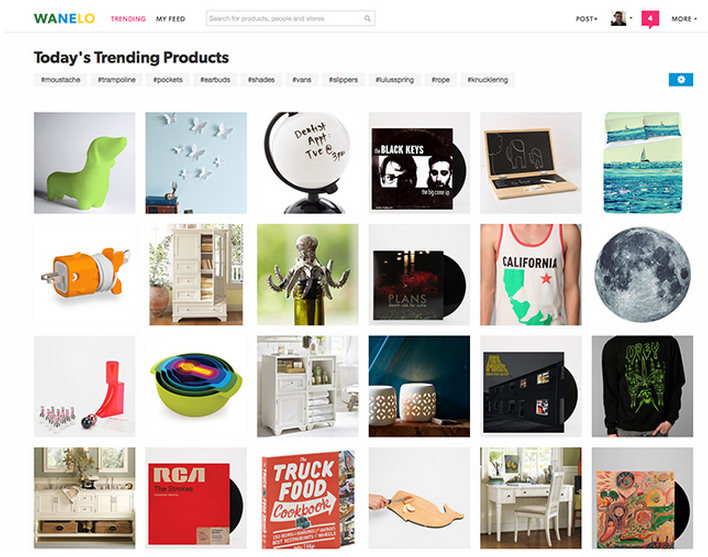

The Wanelo you see today is a completely different website than the one that existed a few months ago. It’s been rewritten and rebuilt from the ground up, as part of a process that took about two months. We thought we’d share the details of what we did and what we learned, in case someone out there ever finds themselves in a similar situation, weighing the risks of either working with a legacy stack or going full steam ahead with a rewrite.

The Cost of Success

Wanelo Version 1

Back in February 2012, Wanelo was a fast-growing online service with some ecstatic members and a lot of promise. The technology stack that powered Wanelo v1.0 was a pretty typical Java-based one: Java 1.5 with Hibernate ORM, Spring and Struts 2 (formerly WebWork), all running atop Tomcat and MySQL 5. When the first Wanelo engineering team was starting, circa 2009, this choice was a big step forward, especially compared to the bloated alternatives of J2EE.

However, the original tech stack served its purpose, enabling the prototyping of various features and allowing Wanelo to gain traction among many of its passionate users. As Java is pretty well optimized on the server, it also offered many reasonable scaling options.

When your CEO restarts Tomcat every thirty minutes…

When I joined Wanelo as it’s CTO, there were only two employees: Deena Varshavskaya (its CEO and Founder) and her sister Kristina.

Literally, about an hour after I verbally accepted the position, I got a call from Deena. It sounded like this:

So this is how my tenure started, and during the first two weeks I had to dive in and fix the performance issues plaguing the site that just got just a little too popular for the teeny tiny Rackspace-leased server, that was housing both the database and Tomcat. Oh, and of course it was serving static assets with Tomcat.

Onward

The New Team

As soon as the new engineering team had assembled, the question of whether or not we wanted to keep the Java stack was a heated topic of discussion. Most of us were familiar with Java and Java-based web frameworks. So much advice around the web leaned toward not rewriting the existing software, but rather extending it incrementally or simply embracing the old platform and "fixing it."

We were well aware though that since Wanelo was (and still is) a young and unproven startup, the most important objective of the technology powering it was the ability to move forward as rapidly as possible and learn, without compromising the future integrity of the underlying platform.

So in choosing our new stack, we were hoping to harness the immense productivity gains promised by the more modern options, in particular those offered by the dynamic languages.

New Stack

Thus, against the tide, and with many reservations, we made the decision to do a complete rewrite.

We chose Ruby as the language, and Ruby on Rails as the underlying framework. The vibrant ecosystem of open-source projects around Ruby was a strong motivating factor, as was our team’s prior experience building successful Ruby-based web apps. We were also keen to switch from MySQL to PostgreSQL, for many well-publicized reasons.

From Zero to Launch

Today’s Wanelo is the result of a two-month-long rewrite, and the migration of its data from MySQL to PostgreSQL.

Since that initial launch, we’ve been adding and extending features daily and deploying continuously. The growth of the Wanelo community has continued unabated, and we managed to launch a highly successful iOS app on top of our API layer — all with a team of about 11 people (not all engineers).

Now that it seems to safe to say that our unorthodox approach was validated, we wanted to highlight some of the key data points of this switch.

First, Some Stats

The original Wanelo Java app had about 70k lines of code (100k lines total if you include JSP and XML files). Not all of the code was in use, and there were no automated tests or deployment scripts.

The new Wanelo Ruby app had about 7k lines of code at launch (Ruby, CoffeeScript, Haml, SCSS), and another 5k lines of tests. We’ve since added many new features, and are now at just 11k lines of code and about 8k lines of test code, for a ratio of 1:0.7. So still under 20k lines of code after four months of development.

Our new application is built atop Ruby 1.9.3, Rails 3.2, Devise, CoffeeScript, Compass, Haml and SCSS, and it uses PostgreSQL 9.1, Redis and Solr for search. We use minitest, Jasmine and Capybara for testing, CarrierWave for image handling, RABL for API generation, SideKiq for background jobs, Chef for provisioning new boxes on the cloud and Capistrano for deploying our code. We run our environment on Joyent Cloud, store images on Amazon S3, and use Fastly and CloudFront as our image CDN.

Database Layer

The Java app relied on 53 database tables, some of which were still MyISAM, and some of which were InnoDB. Only about 10 of them had a lot of data. The database server performed significantly better after an upgrade to Percona Server, but was still showing a load average of about 4-5 during busy times.

The new PostgreSQL schema contained only 13 database tables upon launch, as we determined most of the MySQL tables weren’t in active use. After launch, we had to add some missing indices on tables, and after that the load on the server settled to about 1.5-2 during high-traffic times.

We spent a fair amount of time deciding how to migrate the data, and writing data migrations. Here’s how that went down.

The Great Migration

Early on we chose the following approach for our data migration strategy:

We would use an existing tool to migrate the schema mostly "as is" from MySQL to PostgreSQL. We’ll call this PostgreSQL schema containing the old MySQL tables the "legacy schema."

-

Configure the legacy schema in database.yml to belong to the "legacy" Rails environment. Use host: localhost to prevent rake from dropping/recreating this schema automatically (only non-remote schemas are dropped automatically).

-

Create a project directory called db/legacy_migrations and add appropriate rake tasks to migrate the database schema using migrations inside that directory. This rake task was called

db:legacy:migrateinstead of the regular "db:migrate." -

Start developing the new Ruby application, and while adding the new schema migrations for the new models, also add the legacy migrations to move the data from the old tables to the new. As we were pair programming, one pair could work on the new feature and a new model, while the other pair worked on migrating the data.

One early finding we bumped into was that the old tables and new tables would have to live in the same PostgreSQL schema so that we could easily copy/transform data using SQL between tables. If we put the legacy tables in another database or schema, it was not as easy to move data between them. This might be a limitation of PostgreSQL. Luckily, our Java application used singular names of entities (such as “user”) while the Rails app uses plural. So we could keep the same names and go from the "user" table to "users,`" within the same database schema.

The second challenge was the actual transfer of data from MySQL to PostgreSQL as is. This proved to be no small feat, as we ended up using a custom-built project with a few rake tasks, on top of the mysql2psql gem. In that mini-project, we used the gem to export from MySQL to *.sql files ready for import into PostgreSQL, but we had to munge some of them first to make them work with Pg. For example, the MySQL ENUM column type was exported as VARCHAR(0), and we had to fix that because Pg did not accept that data type. Similarly, bit(1) columns were not properly exported and had to be converted prior to export into regular integer columns. Luckily, there weren’t that many special cases we had to deal with, and mysql2psql provided most of the functionality out of the box.

We also found that the gem appears to have an exponentially increasing performance penalty based on the number of rows exported. So we wrote a rake task that split all rows in the largest table into chunks of 100k, and then started one export per chunk in parallel, using multiple processes. This allowed us to eventually export data from MySQL into a Pg-acceptable SQL file very quickly (under 30 minutes for a 5GB InnoDB file). Our initial attempts to do so took over 20 hours.

The exported files used PostgreSQL’s "COPY" command, which is very fast. So the import of the files took a significantly shorter amount of time — about 15 minutes tops. Now we just had to run the legacy migrations to populate our schema.

Our switch from from the old stack to the new one took place on June 27, with four hours of downtime (we could have done it faster, but we decided that four hours was acceptable for such a large migration). There were six steps:

-

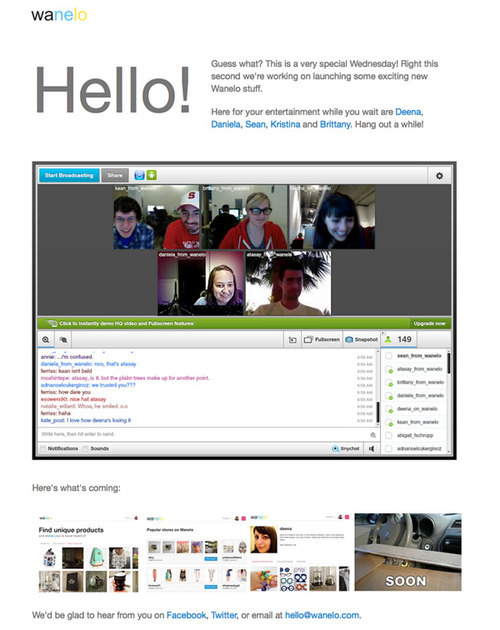

Shut down the old site, and fire up a live video chat on the placeholder page to keep visitors entertained :)

-

Export from MySQL to files, then import those files to PostgreSQL (30 minutes), using several parallel processes and threads working at the same time on different tables.

-

Run the schema migrations (10 minutes) on the new schema.

-

Run the legacy data migrations (1-2 hours), moving data from old tables to the new.

-

Bring the new app up internally and do a quick smoke test.

-

Bring the new app live to the world.

Despite the enormous risk with this type of change, our launch was relatively uneventful. We fixed a few bugs throughout the day, and added a few redirects we had forgotten. But now we were running on a new streamlined platform, highly optimized for rapid development, and built atop the latest version of Ruby on Rails. We were ready for the next phase.

Conclusion

There are several reasons why a complete rewrite worked out in our case. I’ve been thinking about it a lot, and I think it comes down to the following:

-

The old Java codebase was large and difficult to navigate, yet the MVP feature set for Wanelo was relatively small and had an early estimate of 2 months of work with 3 developer pairs.

-

The lack of automated tests in the Java codebase gave us no confidence that by incrementally changing the existing software we would not break anything.

-

Conversely, using test-driven development in the new codebase gave us a lot of confidence about delivered and accepted features.

-

There were only ~10 database tables needing data migration to the new schema. As with the source code, the old schema contained many tables and/or columns that were no longer used, and so migrating the data allowed us to clean things up.

-

It was critical to augment the early engineering team with several experienced Rubyists, who were instrumental in getting the initial set of tools and processes to work together.

-

As the entire team was new, it seemed right to get everyone involved with the new codebase early on, instead of spending cycles learning the old one.

-

We were and still are very lucky to have an absurdly brilliant team.

Hope this post helps you make the right decision in your situation, if you ever find yourself faced with the question of to rewrite or not to rewrite. I hope we’ve proven that in some cases a rewrite is the right choice, but it really depends on many factors.

Stay tuned for more juicy tidbits about Wanelo’s technology and team on this blog.

-http://wanelo.com/kigster[Konstantin]