Good Problems to Have

Wanelo's recent surge in popularity rewarded our engineers with a healthy stream of scaling problems to solve.

Among the many performance initiatives launched over the last few weeks, vertical sharding has been the most impactful and interesting so far.

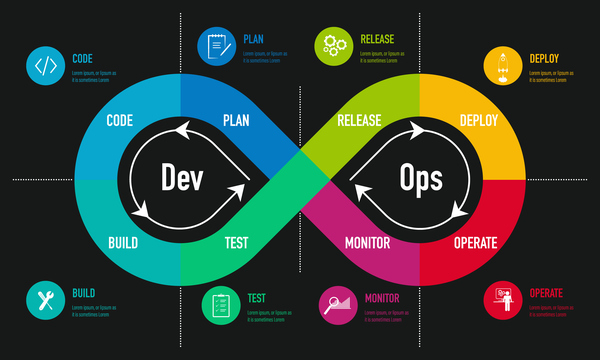

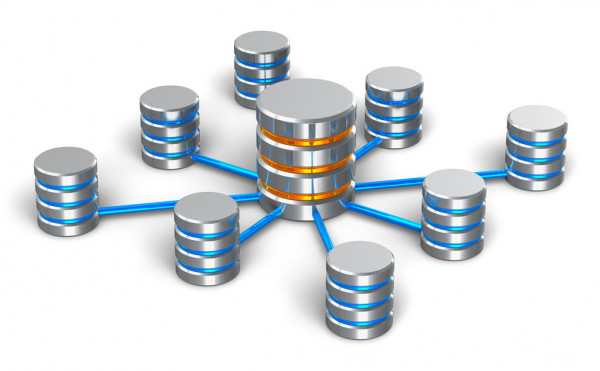

By vertical sharding we mean a process of increasing application scalability by separating out some number of tables from the main database and into a dedicated database instance to spread both read and write load.

Vertical sharding is often contrasted with "horizontal" sharding, where higher scalability is achieved by adding servers with identical schema to host a slice of the available data.

Horizontal sharding is generally a great long-term solution if the architecture supports it, but vertical sharding can often be done quicker and can buy you some time to implement a longer-term redesign.

To the Limit

Under high application load, there is a physical limit on how many writes a single database server can take per second. Of course it depends on the type of RAID, file system and so on, but regardless, there is a hard limit.

Reads are somewhat easier to scale -- multiple levels of caching and spreading reads to database replicas form a familiar scaling strategy for read-heavy sites. Writes, however, are a whole different story.

When a database is falling behind because an application makes too many transaction commits per second, it typically starts queuing up incoming requests, and subsequently slows down the average latency of web requests and the application. If the write load is sufficiently high, then read-only replicas may have trouble catching up while also serving a high volume of read requests.

We noticed that the replication lag between our read replicas and the master was often hovering at large numbers (in hundreds of MBs or even several GBs of data). This manifested to users as strange errors, when rows created on the master could not be found during subsequent requests. 404 pages would be returned for records just created. Even worse, related records created in after_create callbacks would be missing even when the parent record was found, causing application errors.

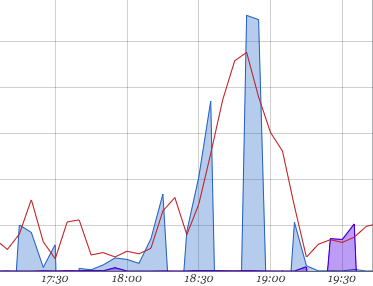

This graph below shows a clear correlation between the number of errors on the site (red line) and replication lag (blue and purple areas). Ack.

Splitting reads and writes made our database layer a distributed system, putting us in CAP theorem territory. While this improved our availability, we realized that we now had to worry about consistency and partition tolerance.

In more practical terms, we needed to reduce the write load on the master to allow our replicas to catch up, especially during peak traffic.

Finding It

We looked at where all the writes were coming from using the amazing pg_stat_statements PostgreSQL library, and it was one of two tables in our schema receiving upwards of 150 inserts per second (our database was doing about 4K commits per second at the time, which can be deduced by comparing xact_commit values in the pg_stat_databases view).

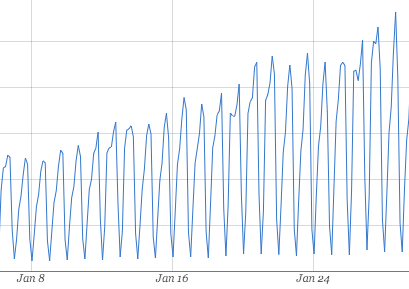

The graph below shows the day-over-day growth of reads on one of the largest tables in our database, and the one we moved out.

This read- and write-heavy table was rather large in size, and also had four indexes on it. For every insert, all four indexes needed to be updated. This meant that PostgreSQL was actually doing more like 500 inserts per second for this ActiveRecord model, if you count each index as a separate table.

Our day-over-day growth projected over the rate of inserts was not sustainable for a database also handling every other type of read and write operation for our application.

So once we identified this table as the one we wanted to split, we put together the following plan.

Doin' It

-

Go through our application code (Rails 3.2) and replace any joins involving this table with a helper method on that model.

-

Each helper method would assume that the table "lived" in its own database, and so queries would be broken up into two or sometimes three separate fetches based on the ActiveRecord model’s database connection.

-

Add an "establish_connection" call at the top of this ActiveRecord model, to connect it to the dedicated database defined in database.yml (even in development, and tests).

-

Go through the app and fix all the broken tests :)

Deployinating It

Here the "a-ha" moment came when we realized that one of the replicas for our main schema could be promoted to be the master database of the new schema.

There were five steps.

-

Configure a live streaming replica of the current master, to be used for the new table exclusively.

-

Take the site down for about ten minutes of planned downtime. Sean ensured our down page had a working kitten cam.

-

Promote the replica into a master role, so that it can receive writes. It was now master for the sharded table.

-

Deploy the new code.

-

Bring the site live.

With some followup:

-

Configure a streaming replica for the sharded database.

-

Delete unused tables in the sharded database.

-

Delete the sharded table from the main database.

Measuring It

After the deploy we discovered that the new master database needed to have analyze run on the table for it to perform adequately, although it was also just warming up the filesystem ARC cache. After that initial warming period, the site hummed along as usual and the next day we were greeted by dramatically dropped I/O on all databases involved, a much faster website latency, and more blissfully obsessed users than ever.

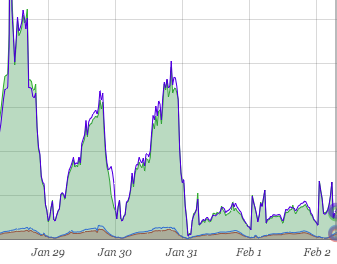

In this graph below of virtual filesystem reads and writes on our master database, you can clearly see where the the sharding happened. There is a dramatic drop in both reads and writes.

While this provides us with some room to grow, we know that sharding this large table horizontally is just around the corner.

Understanding It

Some of the reasons why vertical sharding works may be obvious, but some may be less so:

-

Writes are now balanced between two servers.

-

Fewer writes to each database means that there is less data streaming to read-replicas. These now have no issues catching up to the master.

-

A smaller database means that a larger percentage of the database fits in RAM, reducing filesystem I/O. This makes reads less expensive.

-

Filesystem I/O can be cached in the ARC more efficiently, reducing physical disk I/O. This also makes reads less expensive.

-

Database query caching is now tuned to the load of each database. Radically different access patterns on a single database causes cache eviction.

Thinking About It

As we keep growing, this table is destined to become a standalone web service, behind a clean JSON API which will provide an abstraction above its (future) horizontally sharded implementation. Who knows what data store it will use then. We’re big fans of PostgreSQL, but that’s the beauty of using APIs — whether it’s PostgreSQL, Redis, Cassandra or even a filesystem datastore, the API can stay the same. Today we made a small step toward this architecture.

Feel free to leave a comment with questions or suggestions.

Endnotes

We use PostgreSQL 9.2.2 and are happily hosted on the Joyent Public Cloud. We run on Rails 3.2 and Ruby 1.9.3.

For splitting database reads and writes to read-replicas, we are using Makara (TaskRabbit's open-sourced Ruby gem), which we forked for use with PostgreSQL.

-http://wanelo.com/kigster[Konstantin]